March, 1918

The winter of 1917-1918 had been a relatively quiet time for the Australians on the European front. However, the second Russian Revolution of October 1917 had led to a peace treaty between the Bolsheviks and the Germans, and once this had been enacted, it meant that the German army could reinforce its western front. The long-expected German spring offensive began on 21 March 1918.

FROM EUROPE

The 10th Battalion did repel a German raid on its position early in the month, but no major battle information was surrendered. They cycled in and out of the frontline in western Belgium during the month.

Lou Avery wrapped up his training in England early in the month, and was deeply affected by the German Zeppelin raids over London, which outraged him. Sadly, we bid farewell to him as a correspondent after this time. His diary ends at 12 March and his final entry is a reflection on his views about war and his part in it. ‘Though I voted for conscription, I can now see plainly whey the A.I.F. in France voted against it, It would be terrible to think that doe to our action we had forced one single human being to leave Australia against his will to go through all that we have had to put up with…’ Lou did return to France. He survived the war and returned to Australia and worked as an engineer. His war service history can be found on the National Archives website.

James Churchill-Smith was also training in England during March. He celebrated the second anniversary of the founding of his battalion (the 50th, which was formed in the Middle East at the doubling of the AIF following Gallipoli, and before the AIF joined the European front) and boozy dinner got him into some trouble. The lectures and training were broken up with dinner and theatre, but by the end of the month he was back France on the way to rejoin he battalion.

Leo Terrell spent the month in northern France, and was in and out of the increasingly active front lines. People who have followed Leo’s story from the beginning will know that he was a reluctant recruit, and had never embraced military life. He ended the month by again applying for discharge from the AIF.

Ethel Cooper was still stuck in Germany. We know that rationing had made life almost impossible for civilians: she describes the soap she has been able to source as making things’ fairly clean, but [it] simply reeks of dead fish’. She also notes the glowing German news reports about their successful offensives on the western front, and the impact of this news on the small English community left in Liepzig.

IN THE MIDDLE EAST

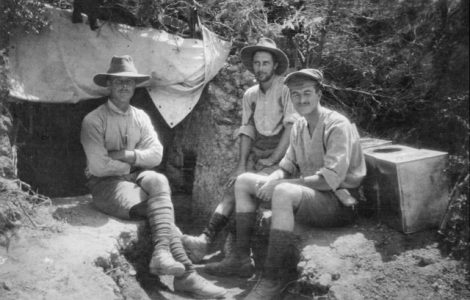

Ross Smith’s diary (held at the State Library of SA) ran out in February 1918, but we still have some of his letters to his mother which share some of his activities, including the physical experiences of flying at 19,000 ft, and some ‘unofficial’ bomb drops. He was still flying above the Middle East, reporting on military movements of the enemy. He was unimpressed by a visit to Jerusalem, but appreciative of a parcel from home containing cigarettes, socks and a hankie.

ON THE HOMEFRONT

Recruitment numbers reached their lowest ebb in March 1918 – only just over 1500 nationally. The fundraising for the war effort and to support the returned soldiers continued, with a ‘Patriotic Display’ at Payneham and a new Red Cross Tea Rooms opening at Mount Lofty amongst the variety of events and activities reported in the Advertiser.

In other news, there was continuing industrial action at Port Adelaide, and it was reported that the price of bread was to be controlled by the Federal Government. Nellie Melba was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire and there was also a story noting that the British Government would accept homing pigeons for use at the war. State Parliament was dissolved in preparation for an election on 6 April.

In war news, the likelihood of a significant German offensive was reported, and also the progress in the Middle East, the subject of Alexandrine Seager’s poem.