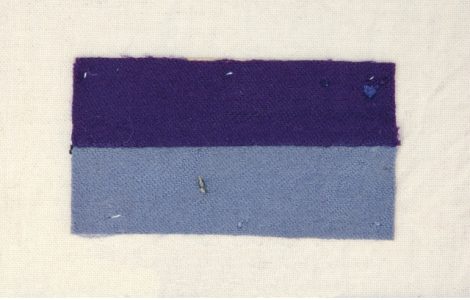

Tank H52, 8 Battalion, 'C' Company, Royal Tank Corps, suffered a direct hit at the Battle of Hamel on 4 July 1918 and was put out of action. [AWM E03843]

People

Churchill-Smith, James, Terrell, Frederick Leopold, Cooper, Ethel, Smith, Ross

Organisations

July, 1918

It wasn’t apparent at the time, but July 1918 was a turning point. Despite the successes of the German offensives of the preceding months, morale in the German army was low, and their losses had been heavy. On the Allied side, on the other hand, there were a million new American troops in the field.

It was during early July that Australian commander John Monash led an attack of Hamel, near Villers-Bretonneux. New, more agile tanks played a significant role in this battle. Monash had at his disposal tanks, infantry, artillery and air power. The battle-plan was shared with officers on 30 June, and was put into action on 4 July, with American troops participating. Within 93 minutes, the objectives were gained. Further Allied offensives later in the month marked the end of the German advance. The 27th Battalion (sometimes known as Unley’s own, for the large number of recruits from the Unley district) played a significant role in this battle.

Our correspondents were not directly involved, but James Churchill Smith did mention Hamel in his diary, and he could see the barrage from his position. When out of the lines, he seemed to be quite enjoying himself – his diary records a ‘very excellent’ six course meal, concerts, swimming, boxing and rowing. Towards the end of the month, he was unwell again, suffering from a rash that he hoped would not keep him from joining his company when they took over from the French at Villers Bretonneux.

The 10th Battalion was further north, in the Merris sector, where they too were in and out of the front lines. Towards the end of the month, the diary reports that Merris was captured, with few casualties. The appendices for these diaries include information about treatment of prisoners, and warning for all ranks about not ‘carrying letters or documents which will supply information to the enemy if captured.’

Ethel Cooper’s diary records that the Spanish influenza was very wide-spread, but that the symptoms were only mild. She does, note, too, though, that she had heard that it had taken a significant toll on the army.

Of our other military correspondents, Leo Terrell’s diary is only brief, but he arrived back in Australia on 31 July. Rather than joy or relief, his diary records more frustration with the army. Ross Smith sent two letters to his mother in Australia – in one he tells her about visiting the grave of a friend who died at Beersheba, and a monument to all the soldiers who fell in the Middle East. In his second letter, he is most insistent that his mother should not share with the media his letters about ‘those 2 Huns I shot down… If that thing did appear in a paper, I would lose every bit of respect of the fellows here that I have got.’ He was worried that there were some trying to single out his exploits as heroic, while he preferred to fly under the radar.

AT HOME IN SOUTH AUSTRLIA

As the fourth year of the war drew to a close, the charities and fundraisers of South Australia were as committed as ever to their support of the war effort. Australia Day was celebrated on 26 July, which was a focus for all kinds of patriotic activities.

The Advertiser also reported on the continuing recruitment drives, and ran a story about 600 homing pigeons joining the war effort.

By month’s end, with news of Monash’s success at Hamel and the arrival of the American troops, there was a feint sense of some hope, that perhaps the tide was turning.