Crowds gather in Adelaide on 5 August, following the declaration of war by Britain. History SA. South Australian Government Photographic Collection, GN01360.

Glossary Terms

Topics

British Empire, Europe on the brink of war, Wattle Day, Arbor Day, Pre-war Alliance System

People

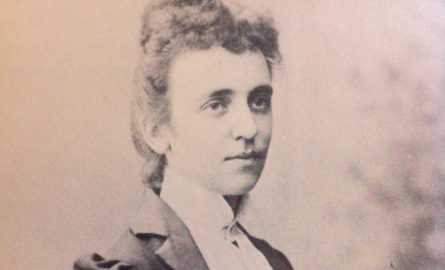

Terrell, Frederick Leopold, Cook, Joseph, Cooper, Ethel, Lady Galway, Franz Ferdinand

Places

Organisations

August, 1914

This month: Meet the first two people whose wartime experiences we will follow and discover how South Australians found out about the outbreak of war and how they responded.

Europe on the brink of war

By the start of 1914 all of Europe was tense. Germany and Britain had been locked in an arms race for decades. The sense of foreboding was palpable – even in far-off Australia. Then, on 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne (Germany’s ally), Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. Around the world the ripples were felt immediately, including in South Australia. A volatile web of alliances in Europe was ready to ignite. Germany’s growing might had been a subject of concern in Europe and Australia for a number of years – particularly with the German colony of New Guinea so close. Adelaide woman Ethel Cooper’s letters from Leipzig to her sister show us just how prepared the German military was for conflict.

Issues in South Australia

Many South Australians, had concerns much closer to home. The state was suffering from an extreme drought causing widespread misery and financial hardship, with many people out of work. Frederick Leopold Terrell, an ironworker, was just returning to South Australia from work in Broken Hill when war broke out. His diary reveals an interest in the events in Europe, but a far greater concern for his own financial future as well as the plight of his friends unable to find work.

War begins

On 1 August, The Advertiser published a hopeful report that diplomatic solutions to the European crisis appeared to be working. In fact, that was the day on which Germany declared war on Russia and two days later, on France. When Germany invaded neutral Belgium on 4 August, Britain was drawn into the conflict, along with the rest of the Empire, including Australia. South Australians gathered in King William Street, anxious for news. The Advertiser reported that everything was ready for mobilisation including motor cars and railway trucks. The paper also reflected on the impact this conflict would have on the South Australian economy as Germany was an important trading partner.

Hardly surprisingly, news of the war dominated the papers in August with lengthy updates about the state of play every day. Following the first announcement, some 20,000 people gathered in Elder Park in an overwhelming display of patriotism. This fervour continued through the month: when they weren’t singing God Save the King or the Song of Australia at public gatherings around the state, South Australians were declaring their loyalty to the King, and shops enjoyed a roaring trade in flags and badges. The Town Hall was opened daily as a place of public prayer.

On 11 August, the paper reported a call for volunteers for an expeditionary force of 20,000 to go to Europe from Australia. South Australia’s quota was 1,583. Only those who were serving in the military or who were already trained were required. Medical examinations began the following week, and soldiers began to move into camps at Morphettville and Fort Largs. Later that week it was announced that 350 horses were required and a call came for an Australian Army Nursing Service.

Mobilisation for activities on the home front also began. A meeting convened by the Governor’s wife, Lady Marie Carola Galway, founded the South Australian division of Red Cross Australia, initially with a fundraising and support focus. Local branches followed. The Mayor’s Patriotic Fund was launched and women offering to make war comforts were advised that socks, mittens and balaclavas were the priority.

Germans in South Australia

We can imagine the mixed emotions of the South Australians of German descent at this time of patriotic zeal. Many could trace their family’s arrival back to 1837, only a year after South Australia’s foundation. Many German groups made a point of emphasising their loyalty to Britain, and as time passed, many signed up to fight and die for King and Country. Adelaide’s then Mayor, Alfred Allen Simpson, insisted that the loyalty of the Germans in South Australia was beyond question, but not all were convinced. German subjects were required to report to their local police station, and a German steamer in Port Adelaide, the Scharzfels, was captured and the crew detained. The Adelaider Liedertafel unanimously decided to discontinue meetings because of the situation in Europe.

The local scene

While The Advertiser covered events in Europe in great detail, there was still local news to be shared – the impending Federal election on 5 September (a double dissolution) and talk of water restrictions in Adelaide (does anything ever change?). An earthquake in the mid-north made headlines, as did the arrival of Sir Douglas Mawson as part of a Commonwealth lecture tour. Arbor Day was observed in many local schools and Wattle Day – a day to celebrate Australia – was observed at the end of the month.

In short: August was a dramatic month for South Australians. Following a tense lead up, the declaration of war early in the month sparked an outpouring of passionate patriotism, which highlighted the close association that South Australians felt to Great Britain. These events overshadowed the domestic concerns – especially drought and unemployment, but did not eclipse them entirely. For many South Australians, events half a world away did not yet have an impact day to day.