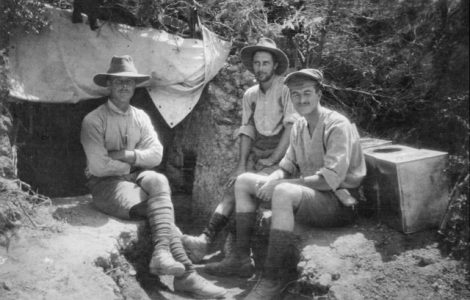

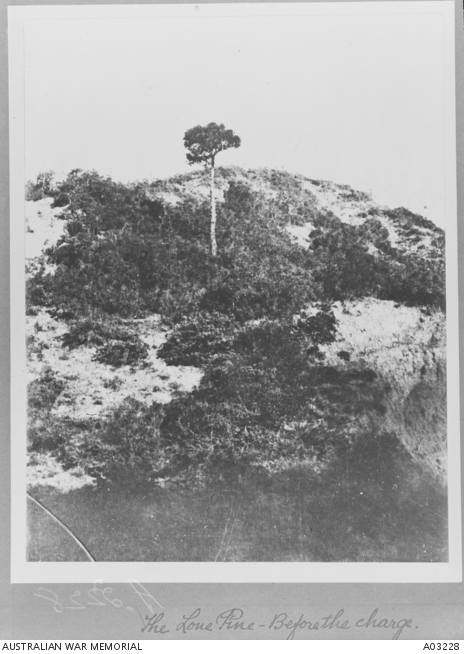

Lone Pine before the charge c Aug 1915 - image courtesy the Australian War Memorial A03228

August, 1915

August offensive in the Dardanelles

Early in August 1915 the Allies launched a major offensive in the Dardanelles in another attempt to secure their objective in providing support for the Russian army, creating more pressure on Germany’s eastern front. We don’t have official diaries from the 10th Infantry Battalion this month (there were no diaries received by the War Memorial Library from August 1915 to March 1916) but three of our correspondents – Lou Avery, Ross Smith and Leo Terrell were all in the Dardanelles and provide powerful accounts of how these events unfolded.

Many thousands of reinforcements took part in the offensive that began on 6 August. An ambitious, multi-pronged attack, it involved New Zealander, Australian, Ghurkha and British troops. The fierce fighting resulted in very high casualties on both sides, but with the Ottoman reinforcements quick on the scene, most of the advantage was quickly lost again. One exception was the battle of Lone Pine – which remained in Anzac hands until the end of the Gallipoli campaign, later becoming the location where the Imperial War Graves Commission reburied many of the dead from across the area. The battle of the Nek also took place in early August. Ross Smith’s regiment was held in reserve as the other three regiments of the 3rd Light Horse attacked. His letter home captures something of the carnage that followed.

Leo Terrell, with the Royal Australian Navy Bridging Train, had his first taste of the war, landing at Suvla Bay with the British to provide Engineering support. We can feel for him as reality hits home.

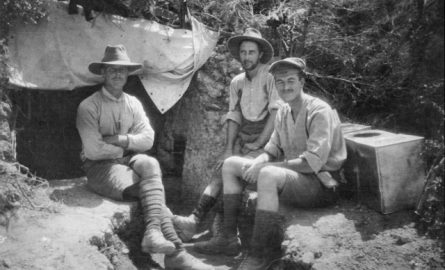

We also meet a new correspondent this week: James Churchill-Smith, a young officer from Norwood who left Adelaide during the month. The difference in tone and focus between his diary and those at the front is marked: with hindsight, we know what awaits him.

In Germany

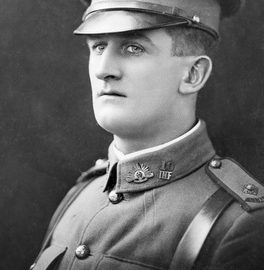

Behind the lines in Germany, Ethel Cooper finally managed to send her letters to her sister in Adelaide. They were smuggled out of Germany by a friend and then posted to Australia. Ethel was also waiting anxiously for news about her friend Sandor, to find out if he was going to be declared fit for military service. She also took a dangerous, unauthorised tour of military barracks – who knows what would have happened to her had she been caught – which she almost was.

The impact of the War in South Australia

Back home, the first of the wounded from the original landings at Gallipoli arrived home by ship. The Advertiser reported that although many had limbs or parts of limbs missing, they were still in good spirits as they were transported by ambulance train to Keswick. More recruits were required by the military and a new recruiting centre was opened by the Governor on Currie Street. Parts of Adelaide Oval were given over for use as a military training camp (although there were no structures on the oval itself, as it was still being used for football matches), while cases of meningitis were reported at the Mitcham Camp. Adelaide City Council accepted a proposal from the Wattle Day League to plant a grove of wattle trees and erect a memorial to commemorate the first landings at Gallipoli.

The paper also carried reports that Australian prisoners of war who had been captured in the Dardanelles were being well treated, but were being worn down by the monotony of their situation.

With the War entering its second year, certain sections of the population were becoming less tolerant of people with German heritage, and the calls to close German schools and Lutheran churches continued. Similarly, those arguing for peace were also the object of public hostility: The Advertiser published a report of police being called to provide protection to a Quaker speaker who was being threatened by an angry crowd.

There was also mention of an increase in the number of illegitimate births, which was also put down to the large number of men leaving for the front. It was hoped that subsequent marriages, upon the soldier’s return, would legitimise these children.

*****

As the War entered its second year, South Australians still read with eager appreciation Charles Bean’s reports of what ‘splendid soldiers’ Australia produced and they continued to donate to the wide array of charities associated with the war. However, the arrival home of the first of the wounded and the ever-growing casualty lists created a sombre tone, as newspaper editorials reflected on the first anniversary of the outbreak with no sense of peace in sight.