October, 1915

October was the month for changing leadership – both at Gallipoli and in Australia.

THE BIG PICTURE

The northern summer of 1915 was disastrous for the Allies. The Russians had lost significant ground, with the German armies occupying Poland and Lithuania; the Battle of Loos, an Anglo-French offensive, commenced in late September. The British used gas for the first time on the battlefield but in places the winds blew it back over their own lines, resulting in more than 2500 casualties. Coupled with the failures of the August offensives at Gallipoli, this disastrous situation meant that there could be no significant reinforcements deployed in the Dardanelles.

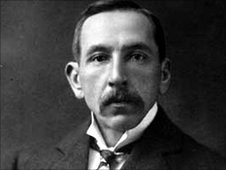

MURDOCH’S LETTER

CEW Bean was Australia’s official war correspondent. He had won this position over Keith Murdoch in a ballot of the Australian Journalists Association in August 1914. However, in early September 1915, Murdoch spent four days on the Gallipoli Peninsula and when he reached London, he wrote a 25-page, 8000-word letter to Prime Minister Fisher detailing the ‘ghastly bungling’ of the British command. He stated that events at Gallipoli were ‘undoubtedly one of the most terrible chapters in our history’. This letter was also sent to British Prime Minster Asquith, who had it printed as a cabinet paper and on 15 October, Sir Ian Hamilton, the British commander of the Gallipoli campaign was recalled.

POLITICS IN AUSTRALIA

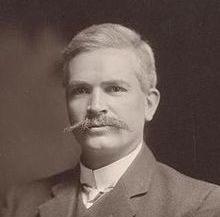

On 27 October 1915, Prime Minister Andrew Fisher made the decision to resign, taking up the position of High Commissioner in London. He was replaced by Attorney-General, Billy Hughes. Hughes was fiercely passionate about the British Empire and vowed to continue to promote British interests.

SOLDIER’S EXPERIENCES

Whilst all this was taking place, the soldiers continued their campaign at Gallipoli. We are reminded that news from the battlefront could take some time to reach Australia; C.E.W. Bean’s report of events at Lone Pine in August were reported during October.

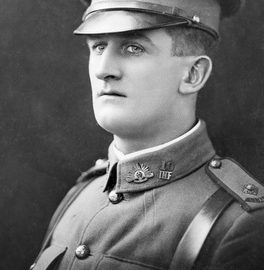

Let’s take a moment to imagine what it might have been like to be James Churchill Smith, who turned 21 during the month. When October began he was in Egypt, enjoying the exotic sights, seeing hippos, rhinos and the pyramids. We can see too, he was learning what it was to be in command of a group of men, as they practised trench drills and attack formations. When he wrote: ‘We will soon be leaving for the front – Hurrah!’, he would have been aware of the newspaper reports about trench conditions in Gallipoli and he almost surely would have seen the daily casualty lists.

Churchill Smith landed at Gallipoli on 24 October. The following day his diary recalls he saw a dead Turk and was fired upon by a sniper. And in this strange world, the next day he met up with old school chums, and witnessed the power of ‘Beachy Bill’. Yet still he writes, ‘don’t think I shall ever get hurt here’.

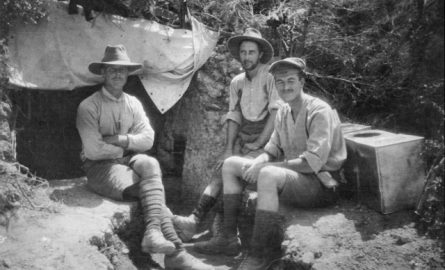

We learn from Leo Terrell’s diary about events at Suvla Bay and his decling health – an eye injury, dysentery and injuries to his hands.

IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA

At home, those with far more serious injuries than Leo Terrell (or, indeed, than Lou Avery, who was evacuated to Egypt last month and who doesn’t record anything in his diary in October) continued to arrive home.

The tireless fundraising continued, led by women such as Lady Marie Carola Galway (the wife of the Governor). In October, the push was for Christmas comforts – small packages to be sent to troops overseas containing items such as tobacco, chocolates and writing materials. The particular homefront environment created by war was affecting social change in South Australia, where it was noted that women’s roles were changing: Lady Galway gave an address to the Chamber of Commerce in October, the first woman ever to do so, about what girls could do to support the war effort. The Advertiser published articles about the appointment of two women police officers and that a female Justice of the Peace had sat on the bench in the Port Adelaide police court. There was also an article on the changes to women’s fashion brought about by their wartime roles.

Alexandrine Seager (who lost one of her own sons at Gallipoli – he died in early August, and the Advertiser carried an obituary in the Role of Honour on 30 September) continued her work with the Cheer-Up Society and to publish her patriotic poems. This month’s verse commemorated 12 months since the first expeditionary soldiers left Adelaide.

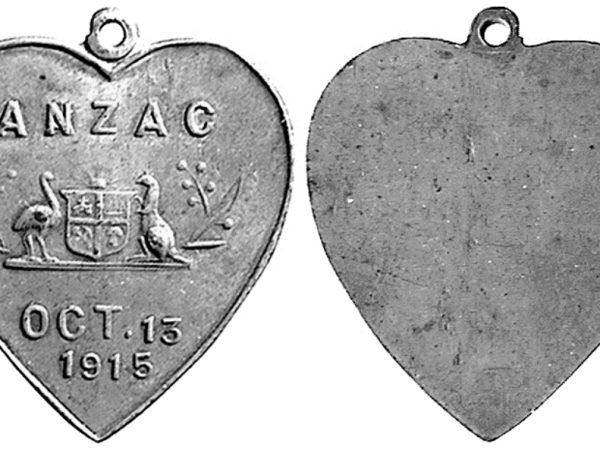

Amidst continuing calls for more recruits and growing community disunity about the need for conscription, South Australians also celebrated ANZAC Day for the very first time on 13 October. A parade from Grote Street preceded a fair at the Adelaide Oval. The Advertiser also reported that munitions were to be fabricated at the Islington Railway Workshops and other locations in SA.

It was also football finals in October 1915. Sturt supporters will be pleased to note their team’s victory (by 12 points) over Port Adelaide. The game was played at Adelaide Oval and watched by a crowd of around 13,000. Parts of the Oval were in use as an Army camp and this was the last game played until after the war had finished.

Perhaps Australians today have a sense of how a new Prime Minister might shake things up. Billy Hughes was certainly a strong personality.