June, 1917

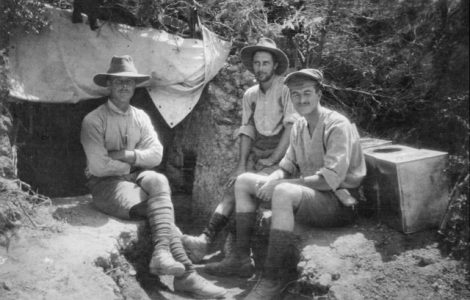

For those familiar with the film Beneath Hill 60 about the Australian tunnelling company and their role in blowing up Hill 60 beneath the Germans, the events of June 1917 will be familiar. A number of our correspondents were involved in the offensive campaign at Messines on 7 June and in the days that followed.

FROM THE SOLDIERS

Messines was two years in the making. Tunnellers had worked underground digging beneath the German lines. It was risky work – the Germans were doing something similar. II Anzac, including the Australian 3rd Brigade under Monash played a significant role in this action. At 3.10am on 7 June, the blast was detonated. It is reported to have been heard as far away as London. Two years after he’d sailed from home, Leo Terrell was part of this battle. From around 90kms away observed that ‘everything trembled… like hell let loose.’ 10,000 German lives were lost, but they still rallied for a counter-attacked, For three days and two nights, Leo records, he didn’t sleep, as gas shells and mortars exploded around him. By this point in the war he notes that his nerves are not as good as they used to be.’ Little wonder!

James Churchill-Smith was also involved in the fighting in the days after. His friend Seager, he notes (the son of our correspondent Alexandrine, founder of the Cheer-Up Society) suffered ‘a slight bomb wound in face’. A couple of days later, his battalion was back behind the lines, playing cricket in the warm summer.

Lou Avery was not directly involved. He was located near Amiens, and spent his spare hours swimming. Bathers were not to be found, so ‘…when the fall is was sounded… many of the boys were in swimming… not to be deterred some fell in naked, others in a hat & shirt…. [The General] was delighted at the strange sight, remarking that it showed good discipline.’ The 10th Battalion was also not directly involved in the initial fighting, but they too joined the fray late in the month.

Far away in the Middle East, Ross Smith was still training as a pilot – his diary notes that he completed his first loop during the month, but he ‘found landing the Avros a little difficult at first.’

BEHIND GERMAN LINES

Ethel Cooper, still stuck in Leipzig, tried yet another plan to be allowed to leave Germany, this time seeking assistance from the Dutch embassy, but plans take time… Alarmingly, her home was raided, with police searching for a diary she was reputed to keep. She writes to her sister about the lucky escape she had with her illegal letters, fleeing to her friend Frau Jaeger’s where she was able to find a safer hiding spot for her weekly letters to her sister. She too, mentions the unusual high temperatures: The drought goes on and the harvest is ruined. Disgraceful enough, when by day you hope that the harvest of 75 million people may fail, and by night that you hope that bombs may fall on the town you are living in, but that is what we have come to.’

AT HOME IN SOUTH AUSTRLIA

The Advertiser was quick with the news of the role played by the Australians at Messines, and effusive with its praise. The same day, though, it also carried a request from Imperial authorities for more nurses. There was also discussion of the regulation and coordination of the various patriotic funds – in previous months we have noted the vast number of funds that operated in South Australia, including the Trench Comforts Fund, the Cheer-Up Society, the Red Cross; early in June their roles were more clearly defined.

On 29 June the Cheer-Up Society held the third Violet Day ‘as a day of memory for Australia’s brave fallen soldiers…’ The Society’s founder, Alexandrine Seager penned the reflective poem ‘Violets for Remembrance’.

The paper also reported on the closure of 49 ‘German’ schools, which impacted more than 1600 children.

How dark must the beginning of winter 1917 seemed for South Australians? With no end to the war in sight, they continued to welcome home the sick and injured from the battlefields, and farewell the fit and healthy from their shores.