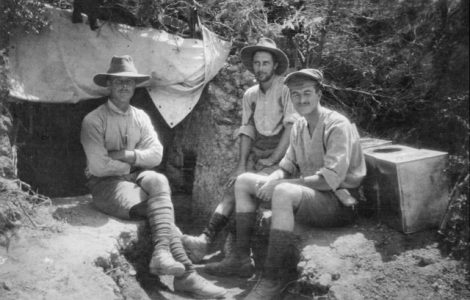

British stretcher bearers - 1 August 1917, Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele) By John Warwick Brooke - This is photograph Q 5935 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums (collection no. 1900-13), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3084107

August, 1917

August 1917: As another year of war ticked over, the sense of war weariness became deeper both at home and on the battlefronts.

Although little was known about it at home in August 1917, one of the largest battles of the War was being waged at this time in Belgium. The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31 July, and the Allied offensive continued through the month, with a staggering 4.3 million shells fired against the heavily fortified German lines. The battle ground received almost twice its usual rainfall, leaving it a sticky quagmire: tanks got bogged and shells failed to explode in the mud.

FROM EUROPE

Australians did not play a significant role in the early part of this battle. Some were drawn in later in the month. For the most part, it was another quiet month for our soldier correspondents, and their diaries give us a sense of the monotony of army life out of the frontlines.

The 10th Battalion spent most of their day marching, drilling and occasionally playing sport. An interesting logistical challenge of army life is revealed in Appendix 6 of the official diary. It notes that ‘All members of the 10th Battalion will bath… and receive a complete change of underclothing… Dirty underclothing to be returned direct to the Clothing Exchange Officer on completion of bath.’ No doubt there were many more unpleasant aspects of war service, but one doesn’t envy that Clothing Exchange Officer in charge of the whole Battalion’s dirty laundry!

Lou Avery also had a bath – ‘About time, too’ he noted. His diary records the official announcement of the beginning of the 3rd Battle of Ypres, ‘after weeks of heavy bombardment’. Discipline, he observed, had become particularly strict. He fell afoul of the Major, who sprung a surprise inspection on them. Lou’s ‘blankets were untidy & a few empty tins were lying about’ so he was included in those who were punished with extra drilling and discipline.

Leo Terrell’s diary records the ceaseless shelling that was going on around him, and he writes of gas shells which keep them awake ‘for one dare not go to sleep while it is about’. He notes sadly on 4 August ‘The anniversary of Britain declaring war… and will go on a deal longer, I think.’

James Churchill-Smith, with the 50th Battalion, recorded in his diary reflections on two personal anniversaries that fell during the month. On the 12th, he noted that it was the one year since the battalion’s first ‘stunt’ in France – the ‘hellish’ battle at Mouquet Farm. It was, he recalls, the ‘only time we have not made a success of a stunt – what we were asked to do was absolutely ridiculous…’. Later in the month he notes the passing of two years since he left South Australia. He spent the last 10 days of August in Ploegsteert Wood, a key location in the Battle for Ypres.

IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Alexandrine Seager was also looking back at anniversaries. She wrote a poem called Romani, recalling the Middle Eastern battle which took place the previous year.

Ross Smith’s diary is fairly short and businesslike in August. He flew a number of different aircraft, and seemed to enjoy trying new tricks. Later in the month he was deployed doing reconnaissance over Beersheba.

BEHIND THE LINES IN GERMANY

Poor Ethel Cooper was almost destitute at this time, having to sell household items to survive. She was still unable to obtain a pass to leave Germany, and her letters to her sister are filled with despair.

ON THE HOMEFRONT

At home, the third anniversary of the outbreak of war was marked by ‘a mass meeting of citizens in Town Hall. The building was filled to overflowing, and the proceedings were intensely patriotic’. In August the 333rd casualty list was published. The Advertiser records farewells for recently enlisted men on the one hand, and welcome home events for others who had been repatriated following injuries. And of course, so many would never return.

Around the nation, the ‘Great Strike’ began to take hold. It began in New South Wales and industrial unrest spread, predominantly through Victoria and Queensland. As the month progressed, more workers joined the protest. In Melbourne, as many as 15,000 working class women took to the streets, and the Advertiser records that Miss Adela Pankhurst continued the family tradition, and was arrested, for speaking too near to Parliament House.

Recruitment numbers continued to fall in August 1917, with only 3274 signing up. Australians were exhausted by the War, which showed no sign of an imminent conclusion.