People

Cooper, Ethel, Avery, Louis Willyama, Smith, Ross, Churchill-Smith, James, Hughes, Billy, Adela Pankhurst

Organisations

January, 1918

As another year of war began, it is not hard for us to imagine that many South Australians had become tired of this war, that seemed to be stretching on and on.

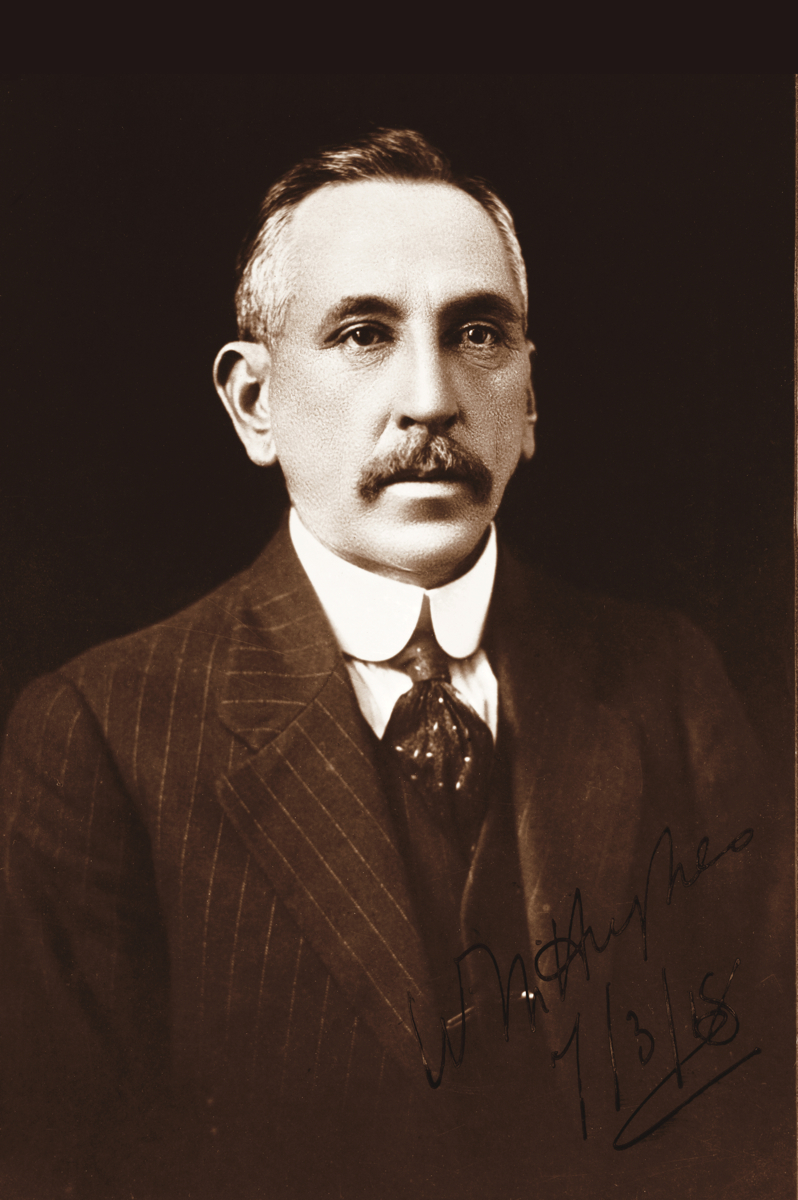

January 1918 – the middle of a cold winter in Europe – was a relatively quiet one for the Australian troops. The real action for the month was at home in Australia, where the Prime Minister Billy Hughes had to deal with the fallout from a second failed conscription referendum held on 20 December. Hughes had said that he would resign if the result came back again as NO, but there was no obvious successor, either in Hughes’ own party, or within the opposition. On 8 January he did tender his resignation, but the Governor General asked him to stay on until an alternative could be found. Several days of negotiations and meetings followed, but no obvious successor could be found, so Hughes – with the support of his Nationalist Party – remained in the job.

FROM THE BATTLEFRONT

Of our enlisted correspondents, Ross Smith was the most involved in the action, in the air above the Middle East. His diary records his first flight in a new Bristol Fighter –‘as good as any Hun’, but also tells the sorrier tale of colleagues killed or captured during air fights in the region. He also explains the process he and his fellow airmen employed for photographing enemy territory from the air: ‘generally 5 photo machines went out & flew parallel to each other about 1000yds apart…’ Later in the month he was responsible for testing a new wide angle camera. It was meant to be flown at 20,000 feet, but at 19,000 the crew decided not to go higher: ‘I’ve never been so painfully cold in my life before, & breathing at that height was quite difficult.

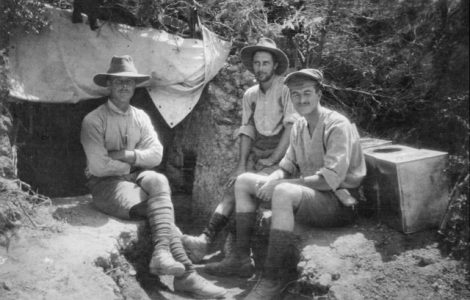

News from the European battlefields this month is limited to the 10th Battalion diary, as Leo Terrell didn’t record anything in January, and Lou Avery and James Churchill-Smith were both in England. The 10th continued cycling in and out of the front lines, but with no significant offensive or defensive action. For the most part, the Allied troops were spending the winter months training in preparation for the German offensives they expected to come in the springtime. Germany and Russia were still negotiating peace following the Bolshevik revolution, but it was only a matter of time before all the troops tied up on Germany’s eastern front would be freed to fight on the western front.

Indeed, Ethel Cooper’s letter to her sister Emmie in Adelaide says that she has heard that a million and a half German troops were being transported by train across to the western front. She also notes that she had made another application for a pass to leave Germany, but again she had been turned down. With very little news from home, Ethel’s good humour seemed to be flagging.

In England, James Churchill-Smith began the month on leave, with daily trips to the theatre. Early in the month, though, he received word that he was to attend Senior Officer Training School – much to his delight. Lou Avery was also still training. He expressed his frustration at having to attend classes to learn how to dig trenches after all of his experience in the field, but he acknowledged that not everyone in the course had such knowledge. He also noted the shortages of food staples such as butter, tea and sugar, but conceded that compared with the ‘civies’ they were doing OK. This month Lou also spent time reflecting on some of the more philosophical questions raised by the war, concluding ‘My opinion is that it has become and industry, a money making concern, & these people do not care how long the war lasts…’ Reflecting on the referendum result, he also expressed his disgust ‘with all those healthy strong young men who stay at home in safety and work themselves into good jobs. The B…. should be made to enlist.’ On a lighter note, he recalled a trip to a nearby town, and a young lady he met who seemed to be keen to ‘catch a kangaroo’. However, he ‘hopped away to safety.

IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA

The Advertiser remained full of articles about the progress of the war, as well as the homefront efforts to support the troops. However, the mood was now decidedly more sombre than before, as more boatloads of injured soldiers returned, and recruitment numbers were low. There was also a report about the reorganisation of the British forces, that meant that the Anzacs were officially no longer in existence. The name, though, had already been burned into the Australian psyche, where it would remain.

In other news, we noted a few months ago that all German place names in South Australia were renamed, and once they were formally gazetted in January 1918, it became compulsory to use the new names. Similarly, we noted that Adela Pankhurst had been arrested and gaoled. In January 1918, she was released early, owing to ill health. There was also an article about the fact that wines grown outside France would no longer be allowed to carry French regional names – so no more Bordeaux.

The brightest news from the papers in January 1918 was the speed at which the American military was recruiting and preparing troops, with almost 700,000 reported as mobilised. Could this effect a crucial turning point?