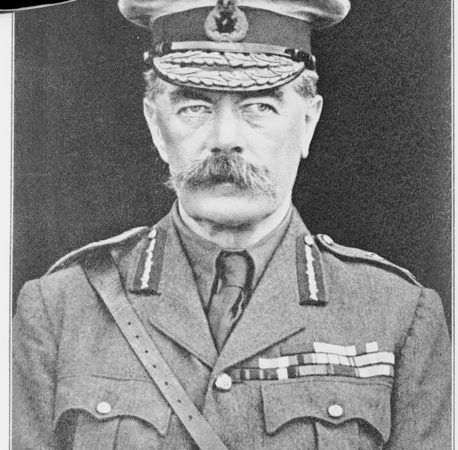

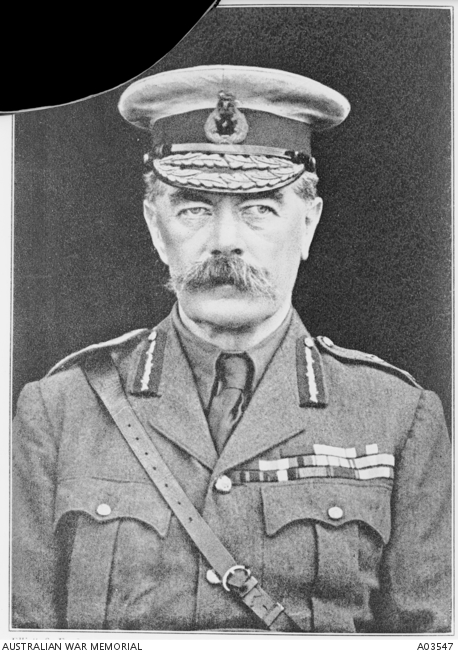

Lord Kitchener, who drowned following the sinking of the Hampshire by a German mine. A03547 image courtesy of the Australian War Memorial

Glossary Terms

Topics

People

Terrell, Frederick Leopold, Cooper, Ethel, Avery, Louis Willyama, Churchill-Smith, James, Hughes, Billy

Organisations

Advertiser, 10th Battalion, Cheer-Up Society, South Australian Red Cross Information Bureau, 50th Battalion

June, 1916

In June, as II ANZAC Corps made their way from Egypt to Europe, South Australians at home were reeling from the news that not only did the British suffer heavy losses during the Battle of Jutland, the most significant naval battle of the First World War, but Lord Kitchener, British Secretary of State for War, had drowned after his ship hit a German mine off the Orkney Islands.

FROM THE SOLDIERS

At the beginning of June, most of our correspondents were still in Egypt. Lou Avery was finally declared fit and was able to re-join his unit as they set sail from Egypt on a ship reputed to have been kept afloat on beer bottles during the Dardanelles campaign. He complained that the ship was overcrowded, but seemed very pleased to arrive in England, where the Australians received a warm welcome as they marched to their training camp on Salisbury Plain. Here, he says, he had his first hot bath since 1914!

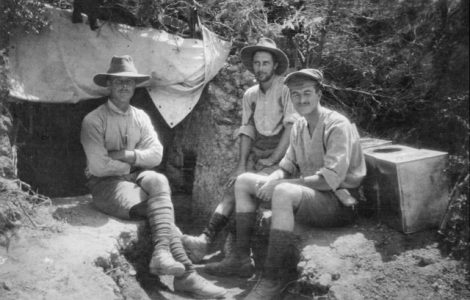

James Churchill-Smith also left Egypt (following what he described as the ‘deverminsation’ of the men’s kits), but he and the 50th battalion were sent straight to France. His diary notes that he was transferred to D Company as Second in Command. Despite the fact that they were on route towards the front, Churchill-Smith took the time to reflect that area around Marseilles was ‘the prettiest country I have ever seen’. After they arrived in their billets, from where they could hear artillery fire in the distance, his battalion were required to undertake bombing training and gas drills.

Leo Terrell, too, arrived in France. Much of the month was spent in transit to their billets near the frontlines and when we leave him at the end of the month, his unit had moved into place behind the front lines.

The 10th Battalion, on the other hand – as part of I ANZAC Corps – had arrived in France in April and on 6 June, the official battalion diary notes that they moved into the firing line, in the northern part of the line. Despite two gas alerts none was detected, but here were a number of casualties from the shelling, as well as acts of bravery under fire noted in the diary. Conditions in the trenches were muddy and wet and although the shelling was comparatively light, it did significant damage to the parapets and trenches, which required constant maintenance. One by one, at the end of the month, the Companies of the 10th were relieved by others, and the soldiers were able to rest.

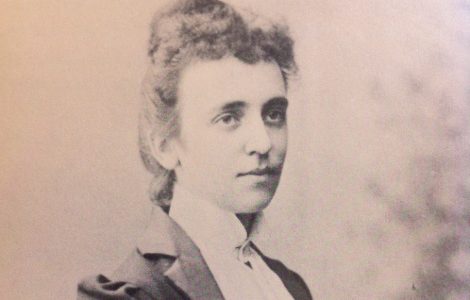

ETHEL COOPER IN GERMANY

From Germany, Ethel Cooper expressed dismay at both the death of Lord Kitchener and the Battle of Jutland in her letters to her sister in South Australia. The food shortages continued but Ethel’s spirits were raised by a visit from her friend Sandor, who had managed to convince authorities that he was better able to serve the German military as a musician, performing fundraising concerts for the Red Cross than as a soldier. She also noted that luxuries such as the theatre were more affordable than the necessities such as food.

IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA

Last month we began following the story of Aboriginal soldier, Private Carter, whose sister contacted the Red Cross Information Bureau seeking news of her brother. Although the Bureau wasn’t able to furnish her with any information, she did receive word from him, assuring her he was well – he’d even seen the Prince of Wales! For now, at least, her mind was at rest. No such luck for the family of Sergeant Alderson, who had received no news since May 1915.

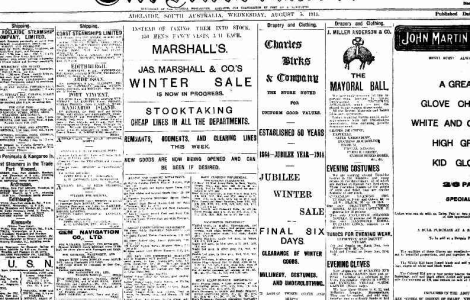

News from the Advertiser during the month tells us that there were record-breaking rains around the state and that there was water flowing in the Torrens for the first time in eight months. There was also an alarming increase in the number of cases of meningitis reported, which was causing authorities significant concern.

Australia’s charismatic Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, was still in England, negotiating on behalf of the nation. He even talked his way into the delegation which attended the Allied Economic Conference in Paris, the only Dominion leader to have a seat at this table discussing potential post-war economic issues.

At home, fundraising for the War effort continued and the Cheer Up Society announced that they would hold another Violet Day in 1916 – this time on 25 August. As the published casualty lists grew, the recruitment drive continued, with publication of some of the findings from the War Census about the number of fit men of enlistment age. Alongside general recruitment, there was a public call for 60 doctors required for service at the front; meanwhile the Governor visited the town of Morgan to unveil a Roll of Honour to the War’s Fallen. There was also an announcement about the impending closure of the camp at Morphettville and another article about a scarcity of hides required for military boots and other equipment.

Of course, news from the battlefields continued to dominate the press, with particular prominence given to reports of the death of Lord Kitchener. There was even a memorial service for him in St Peter’s Cathedral.

In other news, we are reminded that Australia was a relatively new nation and was still seeking a national anthem. The Song of Australia was mentioned as a possibility, but it was noted that in reality, our national anthem was probably still to be penned.

With II ANZAC Corps also now in Europe and Australians again fighting in the trenches, it can be assumed that the casualty lists will again grow rapidly, although the carnage that was to come so soon could not have been predicted.