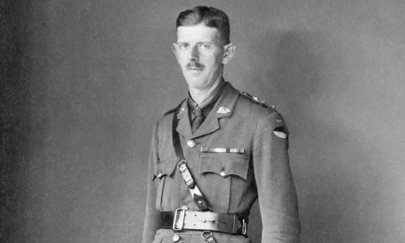

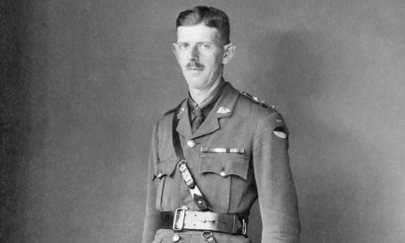

Arthur Blackburn, who was awarded a Victoria Cross at Pozieres.

Glossary Terms

Topics

People

Terrell, Frederick Leopold, Cooper, Ethel, Avery, Louis Willyama, Seager, Alexandrine, Smith, Ross, Churchill-Smith, James, Hughes, Billy, Blackburn, Arthur

Organisations

Advertiser, 10th Battalion, 3rd Light Horse Regiment, Cheer-Up Society, 50th Battalion

July, 1916

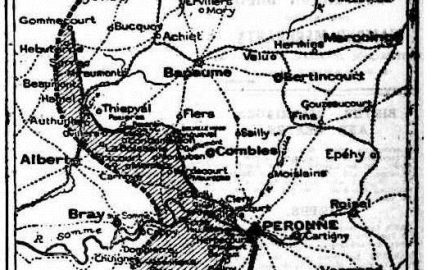

Many Australians are familiar with the events at Gallipoli where, in April 1915, Australians and New Zealanders stormed the beach at Anzac Cove. Despite the odds, they clung to this piece of land for around 8 month before the objective was abandoned and the forces withdrawn. Indeed, it has been argued that our national identity was forged on that battleground. Far fewer Australians know about the actions on the battlefields of Europe, where many, many more Australian lives were lost. The first major battle for the Australians was on the Somme in July 1916, at Fromelles, and then a few days later at Pozieres.

FROM THE SOLDIERS

The casualties from these two battles were horrendous. The official diary of the 10th Battalion provides a detailed account of their role at Pozieres and makes compelling reading. (The July entry is reproduced in full in the link below.) It also recounts the actions of Lieutenant Arthur Blackburn, whose bravery on 23 July was recognised with a Victoria Cross. Colonel Price Weir, the Battalion Commanding Officer ends the entry with a summary of casualties: ‘KILLED 2 officers 56 OR [other ranks]; WOUNDED 11 officers, 235 OR; MISSING 46 OR.

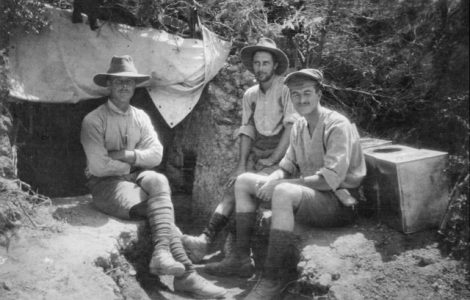

Leo Terrell’s diary recalls the post-battle carnage at Fromelles: ‘This morning found the 8th Brigade back in the same spot as when they left, and many men short. No Man’s Land was a terrible sight: dead and dying everywhere.’ Three days later, back behind the lines, he had his first bath since arriving in France some 27 days earlier. As the month closed, Terrell was on the sick list, with septic sores on his hands brought about, he thinks, by a lack of vegetables.

James Churchill-Smith, in the 50th Battalion, was spared the bloodbath on the Somme for now, instead spending the first part of the month training at a Senior Officers School. He seemed to enjoy the experience, despite an injury (‘strained my right testicule (sic) at bayonet fighting’).

We also welcome back Ross Smith of the 3rd Light Horse. Smith was still in the Middle East in July 1916 and we pick up his story from a letter to his mother about the prelude to the Battle of Romani, which took place in early August.

Our final soldier correspondent, Lou Avery, was in Britain in July, visiting family members in England and Scotland. As the month drew to a close, he was preparing to depart for France.

IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA

Meanwhile, at home in South Australia, outbreaks of meningitis and measles were causing concern and some wild weather left damage around Adelaide, including at Mitcham Army Camp. There were floods along the Torrens (a fairly regular occurrence) and a plan was proposed to divert the river through a new channel to Henley Beach.

The Advertiser reported that South Australia’s third female police constable had been appointed and there was a story about women being employed as boundary riders on a property in the Riverina.

With news from the war continuing to dominate the papers, it was noted that the Somme had replaced Verdun as the focal point on the Western front and when Australians were deployed here much was made of their contribution. Patriotic fundraising activities continued, as did the push for new recruits and the debates about whether Australia should introduce conscription. During the month only just over 6000 men enlisted, yet from the battles of Fromelles and Pozieres, there were more than 10,000 Australian casualties. At the very end of the month Prime Minister Billy Hughes returned to Australia, when the issue of maintaining the AIF at its existing capacity was critical.

FROM GERMANY

Whilst things seemed tough in South Australia, Ethel Cooper’s letters from Leipzig to her sister in Adelaide continue to remind us that the situation for German citizens was far more difficult: food was becoming even more scarce, gold and jewels were being requisitioned by the Government, and even fabric for making clothes and household essentials was available only with a permit.

As July 1916 drew to a close, Ethel Cooper noted: ‘This is the last letter of the second year. It seems like an eternity.’ With hindsight, we know that it the war had not even reached its halfway point.