1914-1915 drought

In the last 100 years the severity of the 1914-1915 drought has often been overshadowed by the outbreak of World War One. It was widespread throughout Australia and particularly prevalent in Victoria, central New South Wales, Tasmania south-western Western Australia as well as in South Australia. Rainfall in early 1914 gave farmers hope for their crops after a long, dry summer. However, as the year progressed, the rain came to a halt and did not return for thirteen long months. The ground became dry and crops began to wither. Stock within the southern states was transported to more suitable areas via railway, causing prices to rise substantially. Throughout various areas of South Australia, May through to October of 1914 remains the driest period on record. By the end of 1914, the wheat harvest was a mere quarter of what had been achieved in the previous year.

1914 SANFL season

SANFL 1914: Port Adelaide not only beat North Adelaide by 79 points in the grand final, but went through the entire season undefeated – a feat never achieved before or since in the competition. A month later, back at Adelaide Oval, Port also beat Victorian champions Carlton in the annual “Champions Of Australia playoff by 34 points.

Arbor Day

Arbor Day originated in Nebraska, USA in 1872 and was initiated by Julius Sterling Morton, who hoped to embed tree planting into the everyday lives of Americans. On the first Arbor Day in America, on 10 April, 1872, an estimated one million trees were planted. On 20 June, 1889 Australia conducted its first formal Arbor Day in Adelaide, with the intention of teaching school children both how to plant trees, and to appreciate their role in the environment and landscape. Children paraded with their school bands from Victoria Square and planted trees in the Adelaide Park Lands, the intention was to give them 'a lesson on the value of arboriculture’ (The Register, 20 June 1889).

Battle of Jutland

This battle, across the space of just 48 hours (May 31-June 1, 1916) near Denmark in the North Sea, was fought between the British Royal Navy Grand Fleet under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and the Imperial Germany Navy High Seas Fleet under Vie-Admiral Reinhard Scheer. Considered the biggest and only full-scale naval battle of the First World War, it was also the last battle of its kind in history. The intention of the Germans was to lure the British into the Jutland Peninsula as a trap, as the Germans had less battleships available to engage the British in open water. The British were keen to continue to ensure open shipping channels for Allied supplies to Europe. After being drawn to the area, the British managed to avoid German submarine attack and surprise the German sea fleet. However, the Germans then made a good pursuit. At the end, both sides claimed they had won the battle. The British lost more boats and double the amount of crew as the Germans, but had contained the enemy fleet. By the end of 1916, the Germans had reinforced its policy of trying to avoid any further full-fleet contact with the British and eventually accepted that it would turn to submarines as their main weapon against Allied ships.

Beersheba

BEERSHEBA: A major city in the Negev desert in southern Israel, Beersheba was occupied during World War I by the Turkish army, which built a rail line from Gaza during 1915. The train system was in active service until 1917, when the British forces, along with Australian and New Zealand soldiers, forced the Turks out of the region. The Beersheba battle on October 31, 1917, was considered an important one in the overall campaign in the Sinai Desert and Palestine. Around 500 Australian Light Horse soldiers, carrying only bayonets, charged at the Turkish trenches and captured them. The action was seen as the final success of a cavalry charge in the history of the British military. Following the war, a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery was constructed, containing dead from Britain, Australia and New Zealand, as well as a memorial park. The British reconstructed the railway, although continuing tensions regarding ownership rights on Palestinian land led to many Jewish residents leaving the city by the end of the 1930s.

British Empire

At the beginning of the twentieth century the British Empire covered almost one quarter of the globe, with territories in all continents and major oceans. It was the largest empire the world had ever known. It included India, Australia, Canada and New Zealand, along with parts of Africa, Asia, and the West Indies. These territories were connected by the Royal Navy – the world’s largest, and a civilian merchant fleet serviced the industries of the ‘Mother Country’ that were supplied by the colonial markets. Many of the people from these territories were fiercely loyal to the British Crown and Empire, and were more than willing to join in a war. George V was crowned in 1910. The grandson of Queen Victoria, he was also a cousin of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. Because of anti-German sentiment, he renamed the British Royal family the House of Windsor in 1917, changing it from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Capture of the German colony of New Guinea

The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF), consisting of 1000 soldiers and 500 sailors, was tasked with the capture of German Pacific Protectorates. The German forces in New Guinea were not large – they were typically used to put down rebellions. Six Australians were killed in the operation, but the AN&MEF were soon victorious. Although this force also had an objective to take control of German colonies further north, plans were foiled, as the Japanese, who entered the war on the side of the Allied Powers in late August, occupied the German colonies north of the equator.

Christmas truce

It had been five months of battle since the eruption of the Great War in August 1914, when the Christmas truce occurred. On 7 December, Pope Benedict XV himself suggested that opposing sides put down their weapons for the celebration of Christmas, and while the warring countries refused an official cease-fire, the soldiers themselves created an unofficial truce. On Christmas day itself, both German and Allied troops left their trenches, stepping into no mans land to greet each other. They sang carols together and exchanged gifts of cigarettes and puddings. Reports reveal that there was event friendly game of rival soccer against one another. However, the truce was not complete across the Western Front, as in some parts weapons continued to be fired and deaths still occurred.

Conscription in Europe

In the late nineteenth century, most European nations had some form of conscription. For example, in Germany, at 20 years of age, men were conscripted into the military for a period of two or three years, although financial restraints meant that in practice only around half actually completed their service. After their training, they were released back into civilian life, but could be called up again up to the age of 45. The most recent trainees were called up first, with those who had finished their training decades earlier filling roles behind the lines. It was a similar system in other nations. In this way, the army was able to expand very rapidly when war was declared in 1914.

Doubling the AIF

Early in 1916, those in command of the AIF had serious planning to do. The successful enlistment campaigns had generated thousands of new recruits, and these men were arriving in Egypt at the same time as those returning from the Dardanelles. The decision was made that the existing battalions would all be split, with half the experienced personnel joining new battalions. Efforts were made to ensure the geographical makeup of the battalions was maintained – so those from South Australia continued to serve together. Thus, over the coming months, the 10th Infantry Battalion would be split to form the 50th, and the 27th to form the 48th etc.

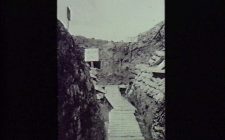

Duckboards

Simple pathways of wooden planks made the muddy, cold & slippery conditions of the Somme easier to navigate.

Eight Hours Day

Eight Hours Day or Labor Day is an annual public holiday celebrating the union victories around creating a reasonable working day for workers. In South Australia, the day involved a street procession of Unions in the morning from Victoria Square, races at Morphettville, carnival at the Oval, children’s sports, grand football match between Port Adelaide (season’s premiers) and team drawn from other league clubs, Whippet Races, Annual Goat Derby, Grand Vaudeville and Picture Show at Exhibition building in evening. Special deals for the holiday like boat excursions, railway timetables, menus. Many visited the art gallery/museum. There were also celebrations in the regions, often involving a procession, carnival, sports events/racing.

Europe on the brink of war

On June 28, 1914 the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was inspecting forces in Bosnia when he and his wife were assassinated by a Slavic nationalist, 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip. This was the second attempt on the Archduke’s life that day: a bomb thrown into the motorcade earlier in the day detonated, injuring one of the royal entourage, but leaving the Archduke unhurt. In an attempt to detour to the hospital to visit the injured man, the Archduke’s open-topped car stopped unexpectedly beside Princip, later in the day, and he took the opportunity to shoot them. Both died within the hour. This event is generally believed to have been a key trigger to outbreak of the First World War, although the causes of the tensions between the two opposed imperial powers, Britain and Germany/Austria, were much more complex and of long duration. Fearing Austrian retaliation against Serbia, the Russian monolith confirmed its support for Serbia. On 28 July, Austria declared war on Serbia, and Russian troops began to mobilise. An alliance existed between Austria and Germany. The Germans had been in a process of militarisation for several decades, and quickly declared war on Russia (1 August, 1914). The Russians were allied with France, and Germany made a pre-emptive declaration of war on France and began to move through Belgium on 4 August to attack France, hoping to end this part of the war quickly, so they could concentrate on the Russian front. However, Britain had already warned Germany that any invasion of neutral Belgium would trigger war, so when the German army entered Belgium, that is precisely what happened.

Federal Election - September 1914

The Federal election on 5 September was called prior to the outbreak of war in August. All of the 75 seats in the House of Representatives and all 36 seats of the Senate were up for election due to Parliament's first ever double dissolution. The double dissolution was triggered when the Labor-dominated Senate refused to pass the Government Preference Prohibition Bill, which sought to abolish preferential employment for trade union members in the public service. At the election, the Australian Labor Party, led by Andrew Fisher, was victorious over the incumbent Commonwealth Liberal Party, led by Joseph Cook. The ALP won the election comfortably, winning 42 (of 75) seats in the House of Representatives and 31 (of 36) seats in the Senate. It was during the campaign, in July, that Fisher gave a speech containing his now famous pledge to support the British War effort ‘to the last man and last shilling’.

First Battle of the Marne

The River Marne, some 30 miles east of Paris, was the site of the First Battle of the Marne in early September 1914. This is generally believed to have been a key turning point in the war, as it prevented the Germans from entering Paris, and from putting the 'Schlieffen Plan' into practice. The Schlieffen Plan had been conceived in 1905 as a strategy for Germany to approach an impending was with neighbours to the East (Russia) and the West (France). It assumed that while Russia was still mobilising troops (a process that would inevitably take some weeks), the German Army would take the French by surprise, approaching Paris through Belgium. This is what happened in August 1914, and the Germans came close to their objective. Although the Allies were successful at Marne in halting the German advance, the cost was high - almost 250,000 Allied casualties, with a similar number of German soldiers killed or injured.

Great Strike

The “Great Strike” of 1917 was actually centred on Sydney, but its effect could be felt across Australia. In the end, close to 100,000 workers, mainly in the railway, tram, wharf and coal mining industries, walked off the job in New South Wales and Victoria for up to six weeks through August and into September of 1917. A fortnight after the union leaders declared an end to the strike, the majority of workers had returned to their jobs. The reason behind the strike was the fact that the New South Wales rail and tram department wanted to introduce a new card system to record and monitor every worker’s input. Scientifically called a “time and motion study”, it was aimed at finding out how long each task might take. However, unions were concerned that this would lead to surveillance of individual workers and thus the potential for bosses to notify and get rid of those deemed inefficient. Average wages across Australia had already fallen by close to one-third by the end of 1916. The attempts by Australia’s government to conscript more fighting men for the war, and particularly the apparent anti-establishment attitude of those of Irish background, also contributed to class tension ahead of the strike. One striker and one strike-breaker were shot. Other members of the general public protested daily in both Melbourne and Sydney, with numbers well into the tens of thousands. To break the strike, the state governments at the time organised volunteer workers from regional areas, university students and school lads to replace those off work. Sydney’s group of volunteers were housed at Taronga Zoo and the Sydney Cricket Ground. By its close, the unions had all but agreed to terms that seemed like a capitulation to the government. Many workers were furious at what they saw as a backdown by the unions. Two of the well-known participants in the strike were Ben Chifley – who would go on to be Prime Minister in 1945 – and Joe Cahill – who would go on to become Premier of New South Wales in 1952. Both men worked in the rail industry. The former was a train driver and the latter a mechanic.

Guy Fawkes Night

Also known as Bonfire Night or Cracker Night on 5 November, this is an annual English tradition going back over 400 years, and until about 1980 was also celebrated in other British colonies including Australia. It commemorated the discover of the Gunpowder Plot of 5 November 1605, when Guy Fawkes (1570-1606), a member of the conspirators was found guarding explosives beneath the House of Lords, ready to blow up Parliament House during the state opening of the new monarch James I’s first English Parliament. To celebrate the King’s survival, bonfires were lit around London soon afterwards and this led to the enforcement of an Act introducing an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure, known as Gunpowder Treason Day. By the eighteenth century it became Guy Fawkes Day, when children begged for money, and effigies of Guy Fawkes were burnt on bonfires. In 1859 the Act was repealed and by the twentieth century, it had become an annual social occasion with the burning of ‘guys’ on bonfires and firework displays, and with little understanding of the historical significance. Due to the increasing number of accidents involving children and fireworks, the banning of Guy Fawkes Night was enforced in South Australia in the 1970s.

Henley on Torrens Regatta

Organised by the South Australian Rowing Association, in 1914 this event was one of the most popular in Adelaide’s social calendar, growing in importance very year since the inaugural event on 17 December 1910. Based on UK’s Henley Royal Regatta held since 1839 in Henley on Thames in Oxfordshire, Adelaide’s version also rivalled Melbourne’s popular Henley on Yarra, formally established in 1904. In the early years of the regatta, the day’s events included not only various races with entries drawn from metropolitan, country and school clubs, but also a procession of decorated boats which were judged by the current mayoress and awarded cash prizes for best and second best. Reserves along the river bank between the City and Morphett Street Bridges were roped off and the public admitted for a shilling where they could enjoy refreshments and other entertainment under the shade of a marquee. It was traditional to wear white with a fashionable hat, and for days prior to the regatta, local shops advertised their latest ‘Henley fashions’. There was also evening entertainment with concerts and dancing, against a spectacular backdrop of illuminated boats, bridges and boathouse, all decorated with coloured lights. Also see Adelaidia for more history http://adelaidia.sa.gov.au/events/henley-on-torrens-regatta

Hindenburg Line

Called the Siegfried Line in German, this was a barrier – built and natural – in various places between 1916 and 1917 from Arras to Laffaux in Eastern France on the Western Front. The original motivation behind building the defences was to ensure a smooth retreat from the Somme, in case the British and French reinforcements proved too much during 1917. The German army was able to rest somewhat after its defeats in 1916, and submarine and aerial bombing were continued against the Allies. However, an overall loss in the war seemed increasingly likely as 1916 turned to 1917. The German forces were short on soldiers, bombs, ammunition and guns and barely two-thirds of the required replacement amounts were no offer by mid-1917. The Germans attempted to negotiate a peace settlement in late 1916 – however their terms as presented included the apparent acknowledgment by the Allies that the Germans were the winners. No wonder it was promptly rejected. The Hindenburg Line – named after General Paul von Hindenburg – was attacked on a number of occasions during 1917 and finally broken in September 1918.

HMAS Sydney defeats the German cruiser Emden

The HMAS Sydney was one of the Australian ships escorting the first convey from Albany in November 1914. On 9 November, the Sydney was ordered to leave the convoy and investigate reports of an unknown ship near the Cocos Islands. It was discovered to be a German Cruiser, Emden, which had been attacking and destroying parts of the British Imperial communication system on the Island. HMAS Sydney, with superior speed, gun range and weight, defeated the Emden. Only 12 Australians were killed in the battle while Emden suffered over 100 casualties. News of the victory was greeted with much celebration by the Australian troops and public. Emden: The SMS Emden, a Dresden-class light cruiser of the Imperial German Navy, attacked a communication post on Direction Island in the Cocos region between Australia and Sri Lanka, on November 9, 1914. Prior to this, Emden had sunk 25 other civilian ships and shelled Madras, India. It had completed the destruction of two Allied warships in the Straits of Malacca near Penang, Malaysia as well. The HMAS Sydney was among a group of Australian, British and Japanese ships sent to investigate the communication post, and the Sydney rendered Emden disabled for battle purposes in under two hours of sea battle. The Sydney crew returned the following day to assist any injured members of the German crew.

HMAT Ascanius

Originally known as the SS Ascanius and part of the British-owned Ocean Steamship Company or Blue Funnel Line (so called because of their distinctive black topped blue funnels), this passenger liner was requisitioned by the Commonweath in 1914 as a troop ship, becoming His Majesty’s Australian Transport (HMAT). It was one of a fleet of 28 Australian and 10 New Zealand transports under a convoy of warships that left Albany, Western Australia on 1 November 1914 carrying the First Detachment of the Australian and New Zealand Imperial Expeditionary Forces.

Italy joins the war

The Italian Government elected not to join the war in 1914 in support of its previous allies, Germany and Austria, instead declaring the country neutral. Courted by both sides, the Treaty of London (which promised Italy territories it had long desired was the inceptive needed, and in May 1915, Italy joined the war on the side of Britain, France and Russia.

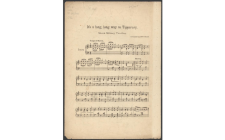

It's a Long Way to Tipperary

The popular music hall song It’s a Long Way to Tipperary became the world’s most famous marching song within a few months after first being reported in a UK newspaper on 18 August 1914. Daily Mail reporter George Curnock was on holiday in Boulogne when he witnessed the Irish regiment, the Connaught Rangers singing this song as they marched through the town after coming ashore. His story was cabled to all parts of the world and soon the song’s lyrics were being reprinted in newspapers, including those in Australia. In today’s parlance, the song went ‘viral’. As well as being picked up by other units of the British army, it was further popularised by its recording by world famous Irish tenor John McCormack in November 1914. The song was written by British songwriter and music hall entertainer Jack Judge (1872-1938) allegedly for a 5 shilling bet in Stalybridge near Manchester, north of England on 30 January 1912 and performed the next evening in the local music hall. However it later transpired that the tune and most of the lyrics already existed in manuscript form as "It's A Long Way to Connemara" written by Judge and his song writing partner Henry James ‘Harry’ Williams (1873-1924).

Leaning Virgin of Albert

Virgin Mary at the top of the Basilica in the French town of Albert. This landmark was hit by a shell on January 15, 1915, and slumped to a near-horizontal position. It was widely discussed that whoever made the statue fall would lose the war. The Leaning Virgin became an especially familiar image to the thousands of Allied soldiers who fought at the Battle of the Somme, many of whom passed through Albert, which was situated three miles from the front lines.

Lewis Gun

A type of automatic machine gun or rifle.

Melbourne Cup

Melbourne Cup: According to www.races.com.au the annual 3.2-kilometre thoroughbred classic was won in 1914 by Kingsburgh (jockey G. Meddick), ahead of Sir Alwynton (A. Wood) and Moonbria (W. Callinan). The odds for the winner were 20-1. Incredibly, Kingsburgh’s owner, L.K Mackinnon, bet on his own horse to win and claimed more than 14,000 British Pounds as a result.

Ottoman Empire in 1914

In its heyday, in the late 17th century, the Ottoman Empire had controlled much of southeast Europe, Western Asia, the Caucasus and northern Africa. Constantinople (now Istanbul) was the capital, and with control over lands around the Mediterranean, the Empire played a significant role in the interactions between East and West. However, the Empire was in decline in the decades leading up to the First World War, losing much of its territory to European powers. It entered the war in November 1914 on the side of the Central Powers, and played a significant role in the Middle Eastern campaigns.

Pre-war Alliance System

The pre-war alliance system in Europe was a major determining factor for the major power’s entering the war. Before the war, alliances were entered into as defensive agreements only. In October 1879 the Austria-Hungary Empire and Germany formed a formal alliance binding the two parties to assist each other, if either was attacked by Russia or another power. Three years later in 1882, Italy joined this alliance creating the ‘Triple Alliance. As a result of the Triple Alliance and Germany’s attempts at becoming a major world power, France, Russia And Britain worked together to form their own alliance system. France and Russia entered into a formal alliance in 1892 that stipulated that if Germany, or Italy supported by Germany, attacked either nation; the other would employ all of their available forces to attack Germany. While Britain had agreed to an alliance with France and Russia, forming the Triple Entente, it would not formally commit to a full military alliance naming Germany as the enemy. Britain did however, commit to an obligation to protect Belgium and her sovereignty. As war broke out and Germany invaded Belgium after implementing the Schlieffen plan, Britain was forced to join the Entente and declare was on Germany.

Race to the Sea

The Race to the Sea was not, in fact, a race north to the coast, but a series of manoeuvres by both the Allied and the German forces attempting to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army. The Germans were hoping to capture the northern ports, and cut off the British supply lines. The British were particularly worried that if the Germans had control of those ports, the German U-boats (submarines) could pose significant threat to the Royal Navy. They too, saw strategic advantage in disrupting the German supply lines. Neither side was successful, and as the opposing forces tracked north, battles were fought in Picardy, Artois and Flanders. By the end of the year, the ‘Race to the Sea’ had ended in a draw, and two lines of trenches had been dug, stretching more or less from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border.

Second Battle of Ypres

The Second Battle of Ypres took place between 22 April and 25 May 1915 and is notable particularly for the first mass use of gas by the German Army.

Sinking of the Lusitania

On 7 May 1915, the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German submarine, sinking off the coast of Ireland. More than 1000 people lost their lives, including more than 100 American civilians. America had declared neutrality in the First World War, and although it took another two years for America to enter the war, this event is considered a factor in the American Government’s decision to join on the side of Britain and France.

Somme Offensive - 1916

Britain’s General Haig didn’t execute any significant offenses in the first half of 1916 but by mid-year a joint offensive with the French was planned for the Somme region, north east of Amiens. The plan was to smash the opposition with heavy artillery fire, destroying the barbed wire in No Man’s Land and driving out the enemy troops from the frontline trenches in advance of an infantry attack. The bombardment began on 24 June, a week before the offensive commenced. Problems with British-manufactured the shells and the guns meant that the bombardment was less effective than planned and most of the German artillery survived. On 1 July, when the British attached they were slaughtered by the Germans machine guns: around 20,000 killed and 40,000 injured. The AIF joined the Battle on 19 July at Fromelles (Flerubaix). The Germans held the higher ground and so could see that an attack was imminent. Again, inferior weaponry and poor communication resulted in very high casualties of both British and Australian troops, and many were taken prisoner of war. In less than 24 hours the Australian 5th division suffered 5533 casualties. Within a few days more Australian troops went into battle at Pozieres. Again and impressive barrage preceded the attack and at 12.30am on 23 July, Australians, including the 10th Battalion began the assault. Although they succeeded in their objective of capturing Pozieres, German counter-offensives forced them back. In four days the Australian division had lost 5285.

Song of Australia

This was a poem penned by Caroline Carleton in 1859, and Carl Linger put it to music. It won the Gawler Institute Patriotic Song competition that year. The SA Register newspaper of October 1859 printed the poem. SONG OF AUSTRALIA There is a land where summer skies Are gleaming with a thousand dyes, Blending in witching harmonies ; And grassy knoll and forest height, Are flushing in the rosy light, And all above is azure bright — Australia! There is a land where honey flows, Where laughing corn luxuriant grows, Land of the myrtle and the rose ; On hill and plain the clust'ring vine Is gushing out with purple wine, And cups are quaffed to thee and thine — Australia! There is a land where treasures shine Deep in the dark unfathom'd mine For worshippers at Mammon's shrine; Where gold lies hid, and rubies gleam, And fabled wealth no more doth seem The idle fancy of a dream — Australia! There is a land where homesteads peep From sunny plain and woodland steep, And love and joy bright vigils keep ; Where the glad voice of childish glee Is mingling with the melody Of nature's hidden minstrelsy — Australia! There is a land where, floating free, From mountain-top to girdling sea, A proud flag waves exultingly ; And FREEDOM'S sons the banner bear, No shackled slave can breathe the air, Fairest of Britain's daughters fair — Australia! It was one of four songs included in a 1977 plebiscite used to choose a new national anthem. South Australians voted it their favourite but overall it was the least popular choice behind “Advance Australia Fair”, “Waltzing Matilda” and “God Save The Queen”.

South Australian election - March 1915

The 1915 South Australian state election was held on 21 March 1915, marking the beginning of a Labor government under leader Crawford Vaughan.

The Australian Landings at Gallipoli

The weather was calm off the coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula (now part of modern-day Turkey) on the night of 24-25 April. Some 40,000 Ottoman troops were on the peninsula, and another 30,000 were nearby. On that morning the men of the Australian 1st Division’s 3rd Brigade (the 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Battalions) were the first to go ashore. Before dawn they left their transport ships, climbed into row boats and were towed towards the shore. At 4.29 am the first of the row boats landed on the shore, and almost immediately the Ottoman’s opened fire. The terrain that greeted them was a narrow beach where steep hills met the water, and the Ottoman forces fired down upon them from these hills. The order was for the troops to push forward towards the third ridge – the target for the first day. Within 15 minutes some had reached the top of the first ridge point. The second wave of Australian soldiers was now arriving onshore, and with the element of surprise now gone, they were met with heavy fire. Upon landing, they too began to fight their way up the hills towards their objective. At 5.30am, the commander of the 3rd Brigade, Sinclair-MacLagan made an assessment that the third ridge was too distant to capture immediately and decided to consolidate his troops on the second ridge. Casualties from the landing and the first day’s fighting were significant. It was difficult to set up casualty clearing stations that were protected from enemy fire and there was enormous pressure on stretcher bearers, who lacked adequate equipment and the suffering of the wounded was significant. About 2000 wounded were evacuated overnight on 25-26 April. Over the following days, the Ottomans launched a number of counter-attacks, but the Anzacs held their positions. On 1 May, four Battalions from the Royal Naval Division had come ashore as reinforcements, and the exhausted Anzacs were about to withdraw and regroup. Meanwhile, the Ottoman forces, under Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) responded with reinforcements and repositioning of artillery. CEW Bean noted that South Australians Arthur Blackburn and Philip Robin probably penetrated further inland than anyone else on that day

The Plan for the Dardanelles Campaign

The Dardanelles campaign was part of a plan to challenge the Ottoman Empire in a move designed to assist the Russian army and ensure that the Russians could export much needed produce by sea. From the outset, it was a controversial plan, with the geography of the region creating many challenges. In March 1915, a British and French fleet was forced to retreat as it approached the Dardanelles. Rather than abandon the plan, though, British strategists, led by First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George were reluctant to give up an ‘eastern solution’ which might alleviate the stalemate on the Western Front. The Australians and New Zealanders were only one part of the plan, which included British troops landing at the tip of the Peninsula (Cape Hellas) and the French launching an assault on the Asian shore of the entrance to the Dardanelles, opposite the British landing position. The Anzacs were to land along the Aegean coast, about 20 km north of the British. The Australian Government was not part of the planning process, and had no input into the British strategic planning. The campaign was a costly one for the Allies, with estimates of around 45,000 and a further 97,000 wounded (this included approx 8,000 Australians killed and more than 20,000 wounded; while around 21,000 UK and Irish died). By contrast, the Ottoman Empire lost around 87,000.)

Violet Day

Before the poppy became the recognised flower for war memorials, the violet in South Australia, was the 'symbol of perpetual remembrance'. Violet Day was first held in Adelaide on 2 July 1915. Alexandrine Seager, Secretary and Organiser of the Cheer-Up Society, is credited with the creation of the event. For more information, visit http://adelaidia.sa.gov.au/events/violet-day

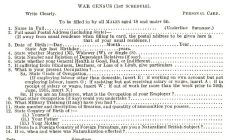

War Census of 1915

The War Census was conducted in September 1915, and required all males 18-60 to complete a 'Personal Card' and all people 18 years and over who possessed property or other income/assets to complete a 'Wealth and Income' card. The 'Personal Card' asked for information about health, occupation, military training and country of birth of the subject and their parents. The 'Wealth and Income Card' sought answers to questions about income, motor vehicles, horses, property, savings and investments. The responsibility for obtaining the forms and for posting the completed forms fell to the individuals. A team of temporary staff was assembled to process the information gathered.

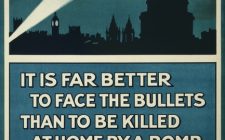

War Loans and Bonds

War loan programs were set up by the Commonwealth and State governments to encourage Australians to support the war effort by purchasing government war bonds which would be repaid with interest. Posters promoting the programs combined patriotism with notions of responsibility to encourage Australians to financially support the war.

War Precautions Act 1914

The War Precautions Act of 1914 gave the Federal Government special powers for the duration of the war and for six months after it concluded. The Act allowed the Federal Government to make laws about anything that related to the war effort.

Wattle Day

The first Wattle Day was held on 1 September, 1910 in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Though plans to celebrate Wattle Day nationally were interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, Wattle Day served as a strong symbol of patriotism during the war with the Red Cross using it as a focus for fundraising for the war effort. The Golden Wattle, flowering during late winter and early spring, grows around the country and is the national floral emblem. Unlike many other national celebrations at the time, Wattle Day was purely Australian, with no ties to Great Britain.