The first Handley-Page 0/400 bomber aircraft to be used in Palestine arriving at the aerodrome of 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial, A00654

People

Terrell, Frederick Leopold, Cooper, Ethel, Smith, Ross, Churchill-Smith, James

Organisations

August, 1918

As the War clocked over four years, it is clear from all our correspondents that finally, finally the tide was starting to turn.

As James Churchill-Smith notes in his diary on 4 August, ‘4th Anniversary of the War – only one more in my opinion as The Huns seem to be losing their hitting powers especially now the allies are doing so well between Rheims & Soissons.’

The Germans were still responding to Allied advances with counter offensives, but it was clear that their dominance during spring had evaporated. The 10th Battalion continued their cycle in and out of the front lines, with battalion baths and fresh uniforms being noted in the official diary.

BEHIND THE LINES IN GERMANY

Regular followers of this blog will remember back to the beginning of the war that Ethel Cooper’s weekly letters home to her sister were full of life and humour. As the war progressed and rationing and scarcity bit hard, her letters became shorter and more downhearted. By late August, though, she writes more hopefully: ‘The two important moments of each day are those when the morning and evening papers come. Then I get out a big general staff atlas and follow the line of our advance over the poor little villages and town that only exist now on maps. It goes slowly when compared to the German rush forward over the same ground five months ago, but it is steady and hopeful.’

IN THE MIDDLE EAST

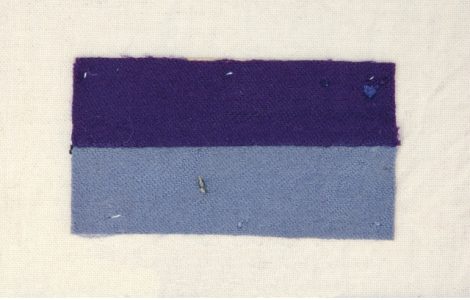

Ross Smith clocked up 500 hours as a pilot, and was thrilled to be given responsibility for the newest plane to arrive on the scene – ‘the big Hanley Page bombing machine’. He had also been awarded a DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross), which is awarded for ‘an act or acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying in active operations against the enemy’, and noted his thanks to his mum for the cable of congratulations she had sent.

Ross had hoped to be granted some leave to return home for a period of time, but his new ‘toy’ proved to be a good substitute.

ON THE HOMEFRONT

Leo Terrell, however, did get home in August 1918. We know that he had been a reluctant recruit, enlisting only because he could find no other employment. Following his transfer from the Naval Bridging Train he had remained unhappy, and had managed to secure a discharge. On 4 August, the anniversary of the start of the war, he records in his diary: ‘Had a real day home, the first for a long time. Had my dear girl with me and life still seems to have something in it worth living for after all.’ Leo is not one for sentimentality of romanticism in his diary, and these words indicate his level of content and relief. He received the formal discharge late in the month.

Meanwhile the Advertiser contained a story early in the month about the execution of the Russian Tsar, who was killed by the Bolsheviks in the middle of July. Amongst general war news and casualty lists, it also contained a story about Private Tomley, who was taken prisoner by the Germans after being injured in April 1917. Almost 4000 Australian troops were captured by the Germans in Europe between 1916 and 1918, and of these almost 400 died in captivity.

Despite the brighter news from the frontline, there was still a desperate need for more recruits to fill the places of the dead and injured, and some units had to be broken up to fill gaps in others.

Good rains in South Australia, too, contributed to a feeling of slight optimism.